Artist spotlight: Lia Pas

Po speaks to multidisciplinary creator-performer, Lia Pas, about textural aspects of chronic pain, slow time, and SciArt.

When speaking and writing on sickness, the trajectory is temptingly linear: a before and an after, a then and a now, a sharp comparative line drawn between the healthy and the unhealthy self. Lia Pas’ biography could easily be divided along these lines: she is a life-long creator-performer who was diagnosed with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) in 2015. But her vast work and meandering mind actively resists this tidy chronicity. Instead, she expresses with slow, sparse, and sprawling gestures, opening space for new and tangential narratives of what it means to live and create with illness.

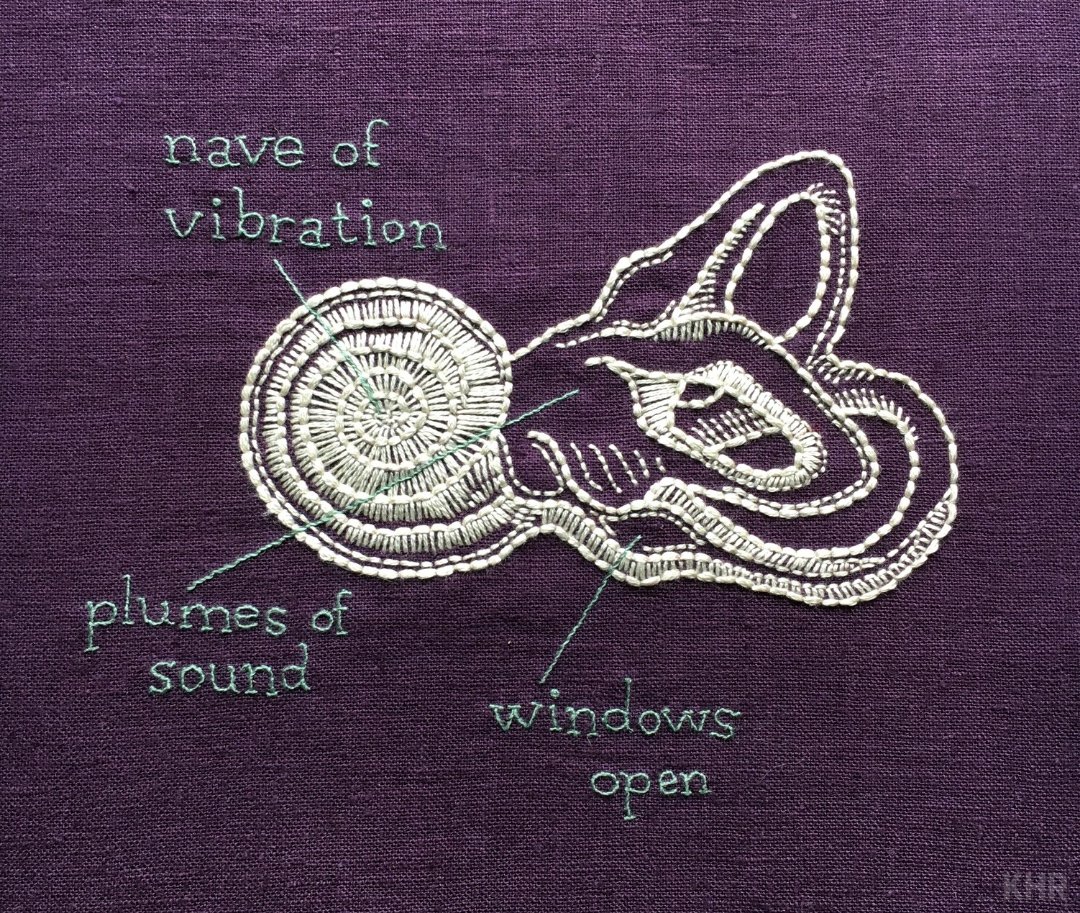

‘nave of vibration’ (2017)

‘neurasthenia’ (2017)

Lia Pas’ craft is astonishingly multi-talented. Performance art, poetry, embroidery, voice work, and music layer together in complex but coherent themes: the body, movement, pain, transcendence, and if you look closely, pleasure. This extensive artistic repertoire is born from her devotion to learning and acquiring different forms of creative expression. Creativity “was always there”. She pauses. “… there’s this recording on a cassette tape of me and my mum and she’s playing ‘Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star’ on the recorder. And I get so angry with her, “you’re doing it wrong.” And I grab the recorder—I’m probably like five—I grab the recorder and I played ‘Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star’ properly. And I just said: “Do it that way.” So. I was very stubborn.”

Lia Pas recounts her life as a series of expeditions punctuated by returns to Saskatoon, Canada, where she was born, grew up, and lives now. Her travels took her to Toronto for her undergraduate in music, and to England to complete a masters in devised theatre. Between this, she taught English in Japan, worked as a professional oboist, played in an experimental improvisation group, learnt and instructed voice work and yoga, and set up her own theatre company. Lia Pas was writing and performing with a dance company in Calgary when she caught a virus: “I just crashed completely from that virus. And it just didn’t go away.”

“Commonly characterised by debilitating fatigue, ME/CFS is in fact a “complex, chronic medical condition affecting multiple body systems” from gastrointestinal to neurological”

Commonly characterised by debilitating fatigue, ME/CFS is in fact a “complex, chronic medical condition affecting multiple body systems” from gastrointestinal to neurological. Its pathophysiology is uncertain but its onset is increasingly linked to post-viral complications like those Lia Pas describes. Despite growing awareness of its severity and prevalence, ME/CFS remains misunderstood and underdiagnosed for both biomedical and social reasons. Medically, symptoms fluctuate in severity and presentation, making them difficult to clinically observe and diagnose. Socially, the illness is notably higher among women than men, with 80% affected being female. The combination of its “elusive aetiology”, fluctuating and often unobservable clinical presentation, and systemic medical misogyny means ME/CFS isn’t allocated the clinical and academic attention proportionate to its severity and prevalence. Many patients receive inadequate and potentially harmful care, like graded exercise therapies, as a result.

“The combination of its “elusive aetiology”, fluctuating and often unobservable clinical presentation, and systemic medical misogyny means ME/CFS isn’t allocated the clinical and academic attention proportionate to its severity and prevalence”

It is in this context that Lia Pas considers herself lucky: “I had an amazing GP who was familiar with ME/CFS” and advised her to “not exercise or exert yourself”. For these first two years Lia Pas was unable to be up and around for more than five minutes. She continued writing some poetry “out of desperation, to be completely honest, because I’ve always been a creative person, and I know if I don’t do creative work, I will get depressed”. From her newfound physicality, she also forged new paths of creativity, asking herself: “I can’t do much, so what can I do?” At the time she “was watching a lot of period dramas because they were calm”, and in one episode, a woman got sick and was told to “take to her bed and work on her embroidery”. She thought “It’s worth a try, why not!” Lia Pas was familiar with fabric and sewing from her theatre training, and she could stitch while reclining: “it was slow enough that I could relax and it was slow enough that my brain could rest, which I think is really important with ME/CFS.”

‘paraesthesia (face)’ (2016)

Taking old anatomical engravings as her inspiration, Lia Pas quickly became hooked; “I couldn’t stop”, she laughs. “I was already interested in anatomy through my yoga teacher training, and my mom’s a scientist, so I grew up with physiological textbooks all over the house.” The medium of embroidery—traditionally reserved for feminine floral patterns—adds a surprising softness to her material interpretation of the body. Many see the anatomical body as having a “grossness about it … you know, it’s disgusting and blood and gore and all that stuff” but Lia Pas finds it “really beautiful”.

Lia Pas now aligns her creative output with a growing movement known as ‘Science Art’ or SciArt. SciArt is a creative, artistic process that intentionally communicates scientific messages or meanings. As an initiative, it intends to “build bridges” between disciplines by highlighting the imaginative competency required in scientific and artistic professions. Like others in the SciArt community, Lia Pas’ art sits between the abstract and emotive and the literal and biomedical. By illustrating sickness through organs, cells, and nerve endings, her work is a frank and raw expression of embodiment. She is at once depicting and “embracing” the unpleasant reality of her symptoms, while also inviting us to see and feel something deeper; “space and beauty” is present, too.

‘endothelial map’ (2016)

“SciArt is a creative, artistic process that intentionally communicates scientific messages or meanings. As an initiative, it intends to “build bridges” between disciplines by highlighting the imaginative competency required in scientific and artistic professions”

Over time, Lia Pas has adjusted the focus, rhythm, and speed at which she creates to move with the waxing and waning nature of ME/CFS. During our call, she holds up a huge half-finished piece titled ‘uterus’ to demonstrate how her embroidered works have been getting progressively and purposively bigger with time; while stitching requires little energy, setting up a piece does. Instead of doing three or four projects at once, she maintains her multidisciplinary output at a dispersive quotidian: “I try to do a little bit of each craft at least once a week”. She records her piano practice rotations on a piece of paper, focusing on a different technique for 10 or 15 minutes every day or two: “piano improvisation, composition, and then learning a piece. I cycle through those.”

“Lia Pas has adjusted the focus, rhythm, and speed at which she creates to move with the waxing and waning nature of ME/CFS”

‘uterus’ (WIP as of 2022)

“while symptoms impinge and impose, they also instigate and expand”

‘body map’ (2016)

But while symptoms impinge and impose, they also instigate and expand. When asked about the mental and emotional changes that came with being sick, she says: “I used to write about the body anyway. But now it’s more … it’s more about the felt sense of what is happening.”

Tapping into “the felt sense of what is happening” requires an ability and willingness to explore uncomfortable sensations: “I already had so many years of meditation and body work”. Her understanding (“and I’m not sure if this is true of everyone”) is that the path through pain “is to go into it. To not ignore it. To go there. And figure it out. Maybe not completely psychologically, but to feel it out. And see, what is it made up of? So often when I’m very symptomatic and when I was really really ill, I would go into my meditations and I was, you know, tingling and in pain and having issues with my breathing and dizzy and all these different things. And I would focus in on the strongest sensation and say: OK, what is this made up of? What is this tingling? What kind of tingling is it? What am I feeling? What am I seeing? I found the deeper I could go into it, the less disruptive it became to me… it no longer felt like a bad thing, it felt like a message.”

These felt messages are offered to others through her art. The response to Lia Pas’ first symptomology piece, ‘paresthesia (hand 1)’, was instantaneous recognition: “people were like, that’s how my hands feel, that’s exactly how my hands feel. I was amazed.” She has had requests from folks with chronic illnesses to embroider their symptoms. Others have brought screenshots of her pieces to their doctors to say: “This is what it feels like.”

“The bodily confines of pain are clear in her anatomically drawn outlines, and the lines, dots, and movements that trace Lia Pas’ symptoms feel uncomfortably familiar and exact in my own skin”

‘paresthesia (hand 1)’ (2016)

As someone living with chronic pain, I am similarly drawn to Lia Pas’ symptomology pieces. Visual depiction provides legitimisation, understanding, and communion that is powerful for those with medically misunderstood illnesses. The bodily confines of pain are clear in her anatomically drawn outlines, and the lines, dots, and movements that trace Lia Pas’ symptoms feel uncomfortably familiar and exact in my own skin. These textured details, however, broaden my language of pain beyond the blunt and two-dimensional tools used to clinically measure dis-ease. Pain is “not one sensation, pain is so multi-layered … there’s different types of pain, and within the pain, there’s different sensations”. Her symptomology pieces both construct and unshackle verbal and visual dimensions of living with chronic illness. In this sense, she invites a pleasure, an expansion, through recognising and honouring constraints.

“Pain is “not one sensation, pain is so multi-layered … there’s different types of pain, and within the pain, there’s different sensations””

‘cell map’ (2020)

“When you’re sick and have to live in the moment, you can’t live up to society’s expectations, and in some ways that’s very freeing”

By communicating freedom through contained, pained stitches, Lia Pas also ruptures an able-bodied chronicity: “when you have fatigue, there’s this paradoxical sense that time has shrunk but also expanded incredibly.” At the end of our call, I asked her to explain. “Well, when you live in a fatigued body, you need to assess what you can do in the moment, so the moment becomes very very tiny. But there’s also the expansion of: I’m so tired, there is no end.” The paradoxical uncertainty that comes with fluctuating and debilitating symptoms creates a “necessary acceptance of the present moment” which makes time both miniature and enormous. “When you’re sick and have to live in the moment, you can’t live up to society’s expectations, and in some ways that’s very freeing.” ‘Cell map’ accounts for pleasure found in the tension between restraint and release: a thickly threaded blue and orange sector is labelled “the firm structure of approach to pleasure” and placed next to a fine and squiggly “where time ran and had pleasure”. Dissecting it like this, Lia Pas’ slow, rhythmic art is a fearless and joyous approach to pain and sickness.

Lia Pas’ work can be found on her Instagram and Website.

More information on and support for ME/CFS can be found here.