From Kyoto to Glasgow: Hopes for the next generation of Climate Leaders

An Interview with Professor Andy Haines

It’s an exciting and overwhelming time to work in climate and health. Just before COP26, the Keppel Health Review (KHR) had a chance to catch up with Professor (“call me Andy”) Haines, who has been a thought leader in the planetary health and climate change field for nearly three decades. We discussed his perception of the 26th United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of Parties (COP26) this year, the changing role of health in climate discussions over the years, and what we need from the health community moving forward.

Andy comes from a clinical background. Back in the late 90s there were not many “health people” attentive to the climate crisis. The Kyoto Protocol—which extended the UNFCCC and commits member states to reduce greenhouse gas emissions—was a pivotal moment. Reflecting back on his time at the Conference, Andy mentioned “I went to the Kyoto Conference in 1997 [and] only a couple of other ‘health people’ were there … I spoke at a side event on the health impacts of climate and the need for climate action”. Fast forward 24 years to COP26 and the health community have become increasingly engaged in climate change and planetary health. Nonetheless, it remains the case that the health systems community is behind the curve. “This is mostly because ‘health people’ are not clear that we have moved past the Holocene and are well into the Anthropocene”. The Anthropocene is the term used to describe the current geological epoch, which began when human activity started to negatively impact natural systems. Andy stressed that the entire model of health was constructed during the previous epoch—the Holocene—and thus needs to be rethought through contemporary frameworks.

Image credit: Unsplash

There are two types of climate action that can be taken to reduce the impacts of climate change: adaptation and mitigation. Adaptation refers to adjustments in ecological, social, or economic systems to reduce climate impacts, and mitigation refers to actions to cut greenhouse gas emissions that exacerbate the climate catastrophe.

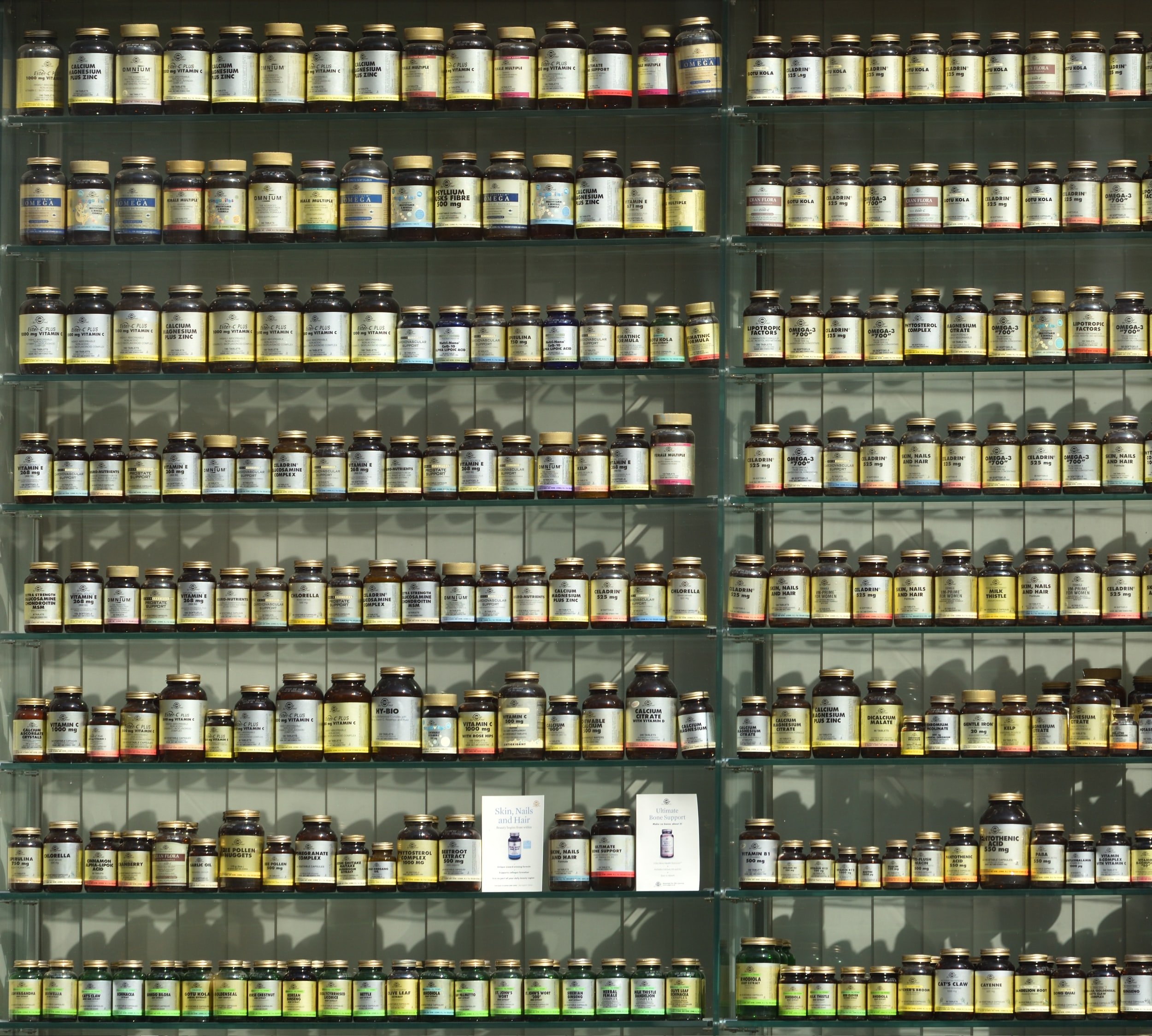

In the past few years, such frameworks and reports have been released to help build climate resilient health systems that can better withstand climate shocks. There is the World Health Organization (WHO) Operational Framework, WHO guidance for climate resilient and environmentally sustainable health care facilities, and most recently the World Bank’s Climate-Smart Healthcare report. These reports also emphasise the need to prioritise mitigation of health facilities, such as the Global Road Map for Health Care Decarbonisation by Health Care Without Harm. Health care systems account for about 4–5% of global greenhouse gas emissions and if they were a single country they would have the 5th highest emissions worldwide. About 70% of health care emissions come from consumption of goods, for example pharmaceuticals or medical equipment.

Image credit: Unsplash

“About 70% of health care emissions come from consumption of goods, for example pharmaceuticals or medical equipment.”

Andy is a big proponent of achieving rapid reductions in greenhouse gas emissions aiming for net zero emissions by 2050 at the latest. Net zero emissions requires a balance between greenhouse gas emissions produced and the amount that is removed from the atmosphere. However, there are concerns that undue emphasis on the potential for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere could delay progress on phasing out fossil fuel burning and other sources of greenhouse gas emissions.

When we suggested that approaches which focus on mitigation and decarbonisation could overshadow adaptation needs in countries that continue to face climate risks, Andy agreed, noting that “we need to get away from the idea that adaptation and mitigation are separate”. Lack of action on mitigation will make adaptation more difficult. A similar point on the need for greater integration of adaptation and mitigation was emphasised during an European Union side event at COP26, and Andy relayed this message, adding that the adaptation and mitigation communities do not tend to communicate.

For high income countries that have high levels of greenhouse gas emissions, mitigation is paramount as they have the resources to reduce emissions in healthcare and other sectors. In comparison, for low and middle income countries that have immediate climate risks to address, the priority is often adaptation. However, as economies grow in low and middle income countries, it is important they do so on a low carbon trajectory. The balance between adaptation, mitigation, and resilience efforts will vary by location. For example, if a community builds a new health facility where there is extreme heat, they could design the building to use passive cooling to make the facility resilient to fluctuations in energy supplies. This would also reduce dependence on fossil fuel energy. It is this type of thinking Andy supports, noting that “we need to think about adaptation actions that do not make mitigation more difficult by increasing greenhouse gas emissions.”

Image credit: Unsplash

The major health benefits will come from greenhouse gas emission mitigation in a range of sectors—for example reduced air pollution from phasing out fossil fuel burning. The food system is responsible for about 20–40% of greenhouse gas emissions—particularly methane from ruminants—so promoting healthy and sustainable diets will have major benefits.

The profile of health has increased steadily in climate change circles over recent years; this year saw the largest health representation yet at COP. Andy expressed the view that there is increasing potential to link health into other sectors to provide solutions beyond the conventional scope of healthcare. However, he was very clear about the breadth of these discussions: “COP is about negotiations, not developing detailed policies”. The interests of all parties at COP26 are conflicting, so negotiations become difficult, especially when there are powerful groups present such as the fossil fuel industries.

Health interfaces with various climate policies, although not in a formal way: “There is a WHO Call for climate action to assure sustained recovery from COVID-19 and COP priorities [on] adaptation, resilience, net zero climate, road transport, green transformation of financial systems … each [of these] has a health dimension. It is also fair to say that there is a growing awareness of health systems as drivers of change … not just in adaptation and resilience but [in] reducing emissions”. This awareness can now be felt across the world, through projects such as the Greener National Health Service initiative and the changing priorities of the National Academy of Medicine in the United States: there is evidently a lot of dynamism in the healthcare sector.

So, what would Andy have liked to see happen at COP26? “On a general level, we want to see health integrated into the climate narrative. The energy sector for example doesn’t see themselves as part of health, but it is, because any decisions made in energy will have massive implications on health.”

“We want to see health integrated into the climate narrative.”

The issue, he continues, is that health outcomes are not incorporated into how other sectors, such as energy, are judged. “Health has a role to reach out to other sectors to say, “you have a health role to play” … [the health sector should also] not forget it is a healthcare sector and should get its own house in order”. He also hopes that Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement—which encompass the efforts by each country to adapt to climate risks and reduce emissions—increasingly reference the health effects of adaptation and mitigation to better integrate the health community into climate discussions going forward: “COP26 is not an end to itself … COP27 will be in Africa—climate justice, mitigation, and adaptation will be key themes where health will need to be represented even more prominently”.

“COP26 is not an end to itself.”

Boat off the coast of Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, where COP27 will take place.

Image credit: Unsplash

With the events of the past two years showing how frail global co-operation can be, Andy asserted that “the commitments countries make at COP need to be implemented—if not they are just hot air.” Further, “guidelines are important … and the synthesis of the best available evidence on adaptation and mitigation is critical. We need evidence of how best to implement these policies and guidelines, with strategies needing to be built from the outset.”

We can only hope that world leaders around the world tap into thought leaders like Andy to speed up actions in time to affect change. The time is now—Code Red.

“The commitments countries make at COP need to be implemented—if not they are just hot air.”

Professor Andy Haines has over 30 years of experience working in environmental health and medicine. He was Director of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) for ten years until October 2010 and has continued on as a Professor of Environmental change and Public Health at LSHTM. Currently he co-chairs the InterAcademy Partnership working group on climate change and health and the Royal Society/ Academy of Medical Sciences group on health and climate change mitigation. He also co-chairs the Lancet Pathfinder Commission on health in the zero-carbon economy that oversees the Pathfinder initiative at LSHTM.