Breaking the silence: enhancing communication on HIV treatments through inclusive social prescribing

In efforts against an epidemic of stigma, Samantha argues that poor communication strategies remain a significant barrier in providing treatment for people living with HIV.

Modern medicine has transformed HIV from a death sentence into a treatable chronic disease. Despite these significant medical achievements, people are still dying prematurely of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and its comorbidities. In most high-income countries, this is rarely for lack of supply of life-changing treatments; instead, it is stigma and non-inclusive communication about treatment options that lie at the heart of this issue.

Image courtesy of Getty Images

Since the discovery of HIV in 1983, treatment has evolved dramatically. With the introduction of the first oral medication in 1987, few could have predicted that less than four decades later long-acting injectable treatments and simple daily drug regimens would be readily available and with few side effects. However, while these medical treatments advanced at a rapid pace, the communication strategies used remained limited. Historically, the communication surrounding treatment options perpetuated the stigma that people living with HIV (PLWH) unjustly faced, with lasting and devastating effects. This included use of words like ‘infected’ to describe patients or assuming that only men who have sex with men (MSM) were able to get HIV. Treatment was focused on opportunistic infections—infections which people with diminished or nonexistent immune systems are more prone to—rather than on the root cause of the immunodeficiency. At the time, HIV was synonymous with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and it was expected that those who contracted HIV would die within a short time span. Furthermore, there was little communication about what options existed for those suffering from AIDS-defining illnesses, such as a unique form of pneumonia (Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia) and the trademark cancerous tumours of the skin indicative of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Communication strategies surrounding early treatment options that were developed in the mid-1990s were naive at best, ignoring the impact that such medications would have on someone’s quality of life. When zidovudine (AZT) was introduced in 1987, there was a glimmer of hope for the PLWH community. Since the advent of HIV testing in 1984, patients were able to discover the illness before symptoms became unbearable, playing a significant preventive role against opportunistic infections. It was at this time that AZT became available and people started living longer, resulting in a drastic reduction in mortality rate. However, it came at a great cost: this treatment option caused consistently reported side effects of nausea, headache, and loss of appetite. It was not known at the time, but AZT was also producing long-term side effects, such as peripheral neuropathy and muscle wasting, and contributing to resistance to future treatment options.

“In this context, finding positive ways to communicate about HIV and its treatment was difficult”

Public perception and communication strategies influenced one another to perpetuate stigma and misconceptions about HIV. For example, one of the earliest campaign slogans for HIV treatment was “hit early, hit hard”, indicating a complete disregard for the impact of negative side effects on the patient’s quality of life. Stereotyping stemmed from the assumption that HIV was a ‘gay disease’, and the word-of-mouth stories of treatment side effects prevented people from seeking care entirely. Many people avoided getting tested for fear of stigma and rejection from their families and friends. Even healthcare providers abandoned medical fact for popular culture stigma, treating PLWH as if they could transfer the virus through a handshake long after such fears were scientifically disproven. In this context, finding positive ways to communicate about HIV and its treatment was difficult, and the few campaigns that existed focused on the MSM community. This exclusion of other at-risk populations, including people who inject drugs (PWID), trans women, sex workers, and immigrants contributed to the continued spread of HIV and the worsening stigma that had now become systemic in the larger population.

“Theatre and the arts became the foundation for educating the public about HIV by way of dynamic storytelling”

Near the turn of the century the work of activists began to change discourse surrounding HIV and communication strategies adapted in response. Broadway musicals cropped up that discussed HIV in a raw and non-judgmental way—Rent, As Is, Philadelphia, and Angels in America, to name a few. Theatre and the arts became the foundation for educating the public about HIV by way of dynamic storytelling, leading to an uptake in testing and treatment. By showing ‘real people’ with HIV, popular culture was an effective vehicle for extending the conversation beyond PLWH and their immediate communities. However, as remarkable as this shift was, portrayals were largely constrained to the MSM community, exacerbating stereotypes and failing to include other impact groups, while only providing a surface-level awareness.

“Although there are now sophisticated treatments for HIV, there is still a lot of work to be done in changing the ignorant assumptions that decades of inaccurate and stigmatising communication have perpetuated”

Although there are now sophisticated treatments with little to no side effects, there is still a lot of work to be done in changing the ignorant assumptions that decades of inaccurate and stigmatising communication have perpetuated. The general population still sees HIV as a ‘gay disease’ and stigma continues to play a significant part in testing and treating those who do not fall into this category. In addition to MSM, the National HIV/AIDS Strategy lists black women, transgender women, youth, and PWID as the priority populations at risk for HIV. These populations, and efforts to communicate about their treatment options, are woefully neglected.

“Despite billboards, digital advertising, street bulletins, brochures from doctors, many campaigns fail to account for risks in pregnancy or target non-MSM communities”

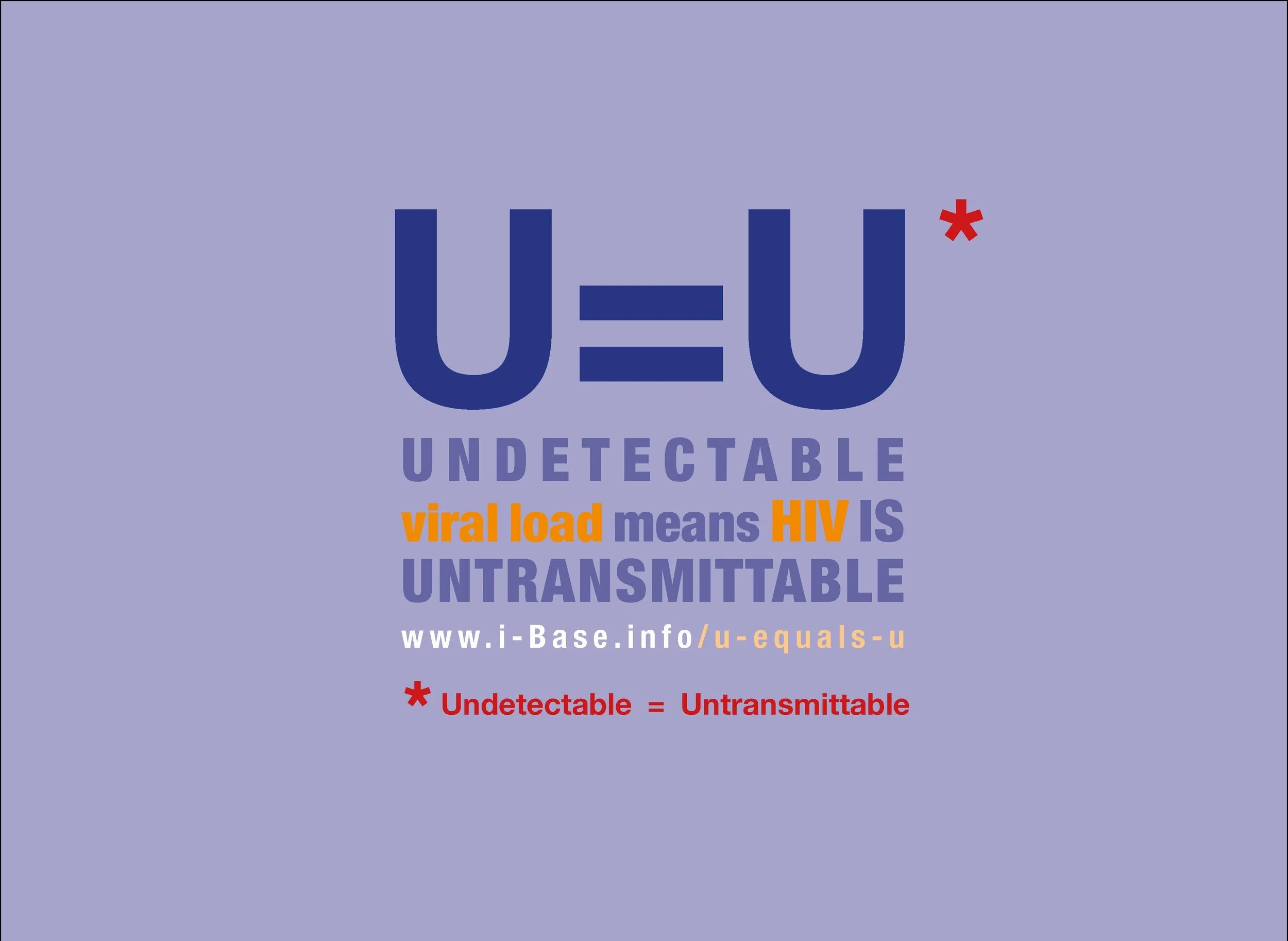

This exclusion is still evident in today’s communication strategies. Despite billboards, digital advertising, street bulletins, brochures from doctors, many campaigns fail to account for risks in pregnancy or target non-MSM communities. Additionally, campaigns such as U=U (undetectable equals untransmittable), which informs the public that someone with an undetectable amount of the virus in their blood cannot transmit HIV through sexual interactions, have demonstrated how information on HIV treatment can be communicated in a harm reduction-oriented way. Although the U=U campaign is focused on transmission of HIV through sexual contact, it has addressed effective treatment outcomes in a way that can empower PLWH to live their lives with little impact from the virus. This is something that needs to be reflected in future campaigns targeting other methods of transmission, such as pregnancy and injection drug use.

Image courtesy of i-base

While many communication strategies remain limited, some campaigns are more successful at reaching and representing at-risk groups. An important component to developing a successful campaign is a concept called social prescribing. Social prescribing alters the way that healthcare providers think about treatment and puts the patient’s values, interests, and hobbies at the centre. PLWH are often isolated and excluded from meaningful activities due to stigma. Through the act of prescribing activities that can bring meaning and encouragement to their life, healthcare providers are able to contribute to the reduction of stigma for PLWH, as well as allow their patients to take control of their own life. Inclusive social prescribing that recognises that the PLWH community is not homogenous can open up treatment options that work for the patient and help to improve HIV treatment uptake. People do not want their HIV treatment to be their whole life, so focusing on empowering them to take part in any activity they want and pursue any dream they may have is critical for their overall wellbeing. Informing patients of sophisticated treatment options, such as Cabenuva or Biktarvy1, can help to increase their capacity to enjoy life unhindered by complicated medication regimens.

“Inclusive social prescribing recognises that people living with HIV is not a homogenous community”

Image courtesy of Getty Images

Another key to developing a successful campaign is ensuring that the strategy is informed by an interdisciplinary healthcare team. Patients who may not easily attend appointments with their prescriber should be able to access information on treatment options through their pharmacies, nurse practitioner-led clinics, social workers, safe consumption sites, and street clinics. There are resources that transient patients access on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis; strategic campaigning should partner with these sources, enhancing awareness and contributing to treatment uptake and consistent access to HIV-related care.

Communication needs to be about regaining control of one’s life, and focusing on ensuring that people can live without the constraints of and reducing stigma surrounding their HIV treatment. People can live a long, healthy life with HIV, and inclusive communication about treatment is critical to managing this chronic disease, displacing stigma, and adopting awareness of the many communities who are impacted.

[1] Since the early days of HIV treatment, hundreds of options have become available for PLWH, such as Biktarvy, a single pill taken once daily that elicits very few adverse effects, and Cabenuva, an injection given monthly to every two months thus reducing pill burden for the patient. While these options may be suitable for many at-risk groups, the prescriber should take into account the patient's own needs to ensure treatment is both empowering and clinically effective.

Abbreviations

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus

PLWH: people living with HIV

MSM: men who have sex with men

AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

AZT: zidovudine

PWID: people who inject drugs