“Why would someone who lives with chronic pain want more pain?” BDSM as a powerful toolkit to communicate and play with messy pain

With guidance from sociologist Emma Sheppard, Po explores the practice of BDSM and the liberation it can bring to those living in chronic pain.

Like many people in their twenties, I am used to feeling a bit rough on Saturday mornings. For the majority, this is a sign of a fun and fulfilling Friday night: the inevitable side-effects of too many drinks and dancing until the early hours. Although my Fridays are mostly quite tame, living with chronic pain means I wake up feeling equally tender and tired regardless. Normally this makes me feel sad and mad: annoyed that my best efforts to pace throughout a week of work and movement have failed right when I have time to enjoy myself.

On a Saturday a few months ago, I woke up to a body hungover with pain. This time, though, I didn’t feel mad or sad—I felt empowered, intrigued, and slightly confused. Newly single and dating, I had hesitantly started exploring the kink scene in London. And that Friday night, I’d met someone who had introduced BDSM play into our relationship.

BDSM is an abbreviation for Bondage, Discipline (or Domination), Sadism (or Submission), Masochism. BDSM scenes often play with power dynamics, in which one or more participant assumes the role of dominating another, who submits consensually to their control through enacting agreed-upon activities. Activities can involve physical or mental control; sensory deprivation; inflicting pain or restraint; and humiliation. BDSM sits within the umbrella of ‘kink’, which more broadly defines “pleasurable activities that people choose to do together that in other contexts are not pleasurable or usual”.

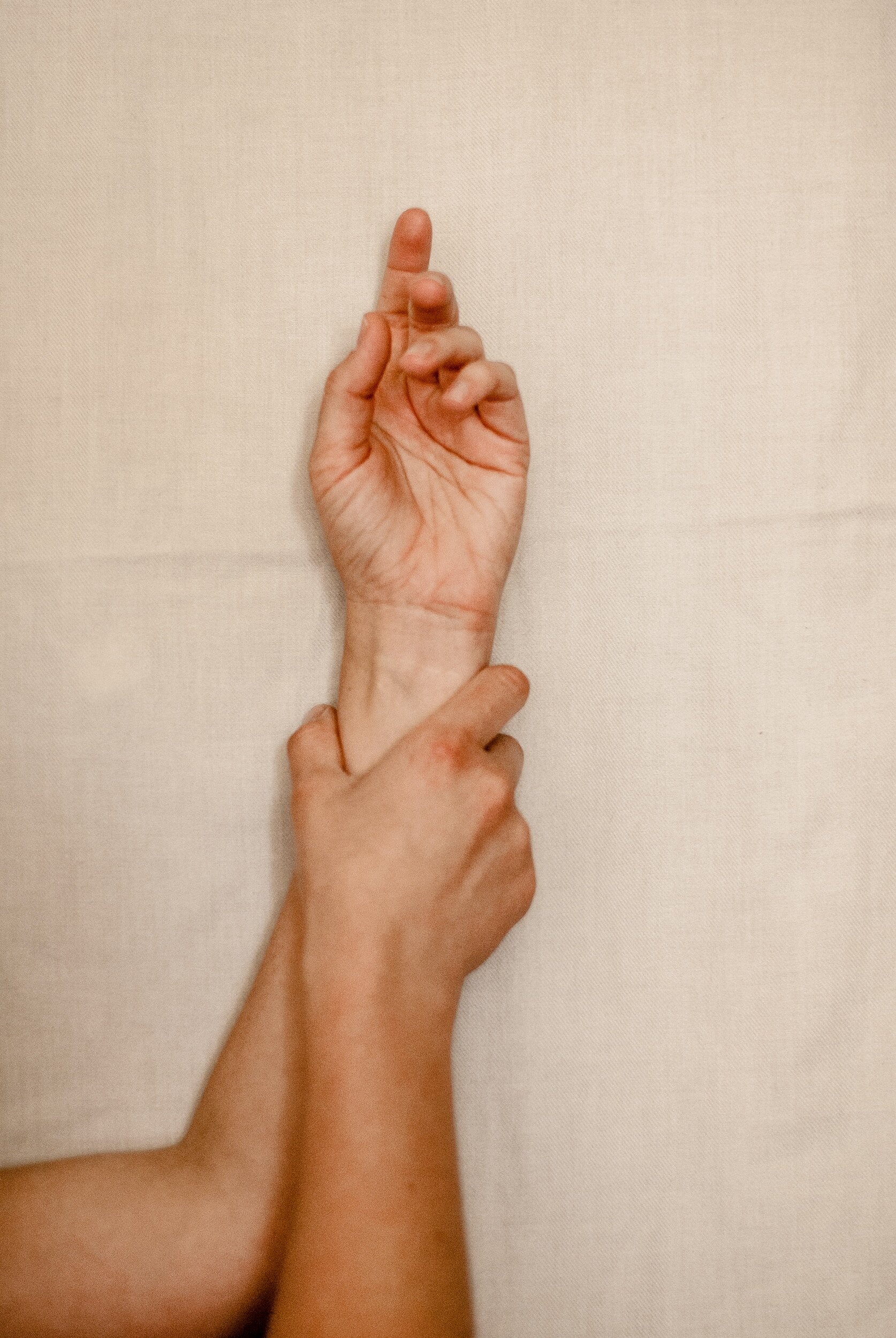

Image courtesy of Unsplash

As a feminist and a person who lives with chronic pain, I never thought BDSM would appeal to me; scenes involving submission to a male-body or masculine performance, and willingly receiving pain, went against all my core values and desires. I’d rationalised my exploration in kink as post-breakup fuelled meta-masochism: I expected to hate it. Even more, I expected to feel used and abused, and for these feelings to intensify my unrelenting anger at our patriarchal ableist culture.

So I was surprised when I not only didn’t feel anger, but pleasure and exhilaration. These curiosities and challenges led me to spend that Saturday under a blanket on the sofa, resting my body and researching BDSM.

I read articles on differing and divided feminist interpretations, queer literature on kink, and watched YouTube accounts that explain, normalise, and destigmatise BDSM practices for people interested in learning to play in a healthy, safe, and fun way. Nothing I read or watched quite aligned with the particular type of power and pleasure I was feeling—one that was not so much intellectual, but distinctly and physically painful—a feeling that neither dense academic literature nor breezy YouTube videos conceptualised. A quick google of ‘BDSM and chronic pain’ churned up a series of articles by Dr Emma Sheppard, a sociologist working on critical disability studies. After an excited read through her article ‘Chronic pain as fluid, BDSM as control’, I immediately emailed her to ask if we could speak. To my joy, she obliged.

“Nothing I read or watched quite aligned with the particular type of power and pleasure I was feeling—one that was not so much intellectual, but distinctly and physically painful”

Emma’s academic interest in chronic pain and kink practices started when she was completing her masters in Gender and Sexuality and working in a sex shop alongside. Responsible for filtering online customer queries, she noticed she was receiving a lot of questions related to disability, like: “Is this sex toy good for people with limited mobility?” or “What is the allergen list for this lube?” In looking for answers to these questions online, Emma found few practical resources. At the same time, she started to interview people about sexuality and disability for her dissertation, and, unprompted, her participants kept bringing up kink. Emma says, “I was like OK, right, let’s look at this”, but when she did, the few bits of academic literature on disability and kink she found “didn’t feel right”. In particular, as someone who lives with chronic pain, Emma was troubled that the “descriptions of the encounters with pain” in both kink and disability literature “just did not fit with what I was experiencing”.

“Pain is often spoken about in medical terms, and with this, ascribed limited temporal and diagnostic parameters”

And so her focus shifted: what is in this experience of pain in kink play for people who are chronically pained? Or, as she asks in her book, “Why would people who live in chronic pain want more pain?” Emma’s findings—through interviewing people living with chronic pain and receiving pain as part of their kink practice—offer important insights into intimacy, sex, and consent. They also help us rethink and advocate for chronic pain as a unique and disabling human experience.

To explain the appeal and joy of painful kink play for her chronically pained participants, Emma argues we have to understand pain better first. Pain is often spoken about in medical terms, and with this, ascribed limited temporal and diagnostic parameters: “you’re either in pain or you’re not in pain”, with the default ‘healthy’ setting as not in pain. But “pain is much more social than we give it credit for”: pain is “shaped by our interactions with each other, our expectations and ideas” in ways that make pain both “fluid” and “messy”. There is thus a disconnect between the messy flux of lived pain and the rigid biomedical language we are provided to make sense of it: acute or chronic; severe or dull; 2/10 or 6/10. With biomedical narratives dominating (pun partially intended) our social understandings of pain, individuals living with chronic pain can struggle to meaningfully make sense of their experiences and needs.

“There is a disconnect between the messy flux of lived pain and the rigid biomedical language we are provided to make sense of it”

Not only do these boxes fail to truly convey and communicate pain as a lived, embodied experience, they curtail our ability to recognise, treat, and honour the role pain plays in our daily lives. Period pain is an excellent example of the limitations of this categorical work. Even though period pain is consistent, regular, recurrent, it is not medically considered as chronic pain, which has been carefully defined as “chronic or persistent pain that carries on for longer than 12 weeks despite medication or treatment”. The repercussions of this definitional demarcation are familiar to many living with chronic pain, who in describing the wax and wane of their pain flares over the course of months, are refused a diagnosis by providers: to not be in pain sometimes prevents a medical diagnosis that arbitrarily demands an always.

“Chronic pain is met with social and medical resistance: we avoid hearing or thinking about chronic pain as if, in doing so, its mess could get on us, exposing the inescapable chronicity of pain in our lived worlds”

Our dogged commitment to attempting (and often failing) to order pain into neat diagnostic categories arguably exposes a collective resistance to hearing and talking about the ugly, messy, fluidity of pain. We prefer these clean biomedical narratives not out of ignorance, but precisely because we are all too familiar with the enormity of pain. Pain is recognised as a sign of “normal, healthy bodymind”—something we have all experienced and been encouraged to communicate. However, pain is also something that should be avoided and “ended quickly when unavoidable”. Chronic pain, therefore, is met with social and medical resistance: we avoid hearing or thinking about chronic pain as if, in doing so, its mess could get on us, exposing the inescapable chronicity of pain in our lived worlds. This metaphor of pain as a “contagion” is not only intellectually appealing; hearing about pain is painful. “As someone who is in chronic pain, I’m not entirely comfortable hearing about other people’s pain”, Emma notes, not missing the masochistic irony of forging a career committed to doing so.

With this new definition of pain as messy, fluid, and contagious, Emma goes on to argue that BDSM offers a unique and often liberating set of tools for her chronically pained participants. Although widely associated with the vanguard and transgressive, it is also important to stress that BDSM is a progressively consensual and carefully choreographed practice. The practice is crafted to permit control, create and preserve boundaries, and most significantly, facilitate communication around pain—aspects of BDSM that appeal for many, but take on unique meaning in the context of chronic pain.

“In most kink scenarios, there’s a scene, there’s a thing you do, there is a beginning and an end. Because pain is so fluid—it gets everywhere, it creeps into every aspect of your life—this experience of ‘bounding’ pain can be really helpful: it puts it in a box and contains it in a space that permits you to interact with it, rather than it being so diffuse it’s almost too much.”

The act of consensually ‘bounding’ pain speaks to common mis-understandings of kink play as an unequal distributon of power to the dominant participant(s). In contrast, many submissives describe an immense power achieved through defining and determining the limits of their own experience. For people in pain, kink can be a liberating space to carve out self-defined parameters within the messiness of pain—ones free from medical pathologisation, and associated with pleasure, connection, and care instead.

Image courtesy of Unsplash

Kink is also an opportunity to consent to pain. Unlike many non-kinky sex or intimacy practices, kink begins with explicit and detailed discussion of capacity and limitation. “Within a lot of kink communities there is an emphasis on talking about capacities and boundaries. Some questions that might be asked are: “What do you like?”, “What do you not like?”, “Where are your limits?”, and “What’s your safe word?”. Kink communities are spaces where these questions are asked regardless of disability-status, and where limitations are common-place and non-taboo: “Oh, so you can be spanked in this area but not in that area”. Emma’s participants felt encouraged and safe to have conversations about boundaries and capacity, without being ostracised by them. People with disabilities are rarely given these tools: we are given a “blue badge” to separate us, but not so much as a “leaflet on how to talk about disability to people you wish to be intimate with”.

And this brings us to the last and most important tool Emma identifies in her work: BDSM provides language to talk about and witness pain. Kink is “a space where being in pain, and expressing pain, is welcome”. Given the social resistance to hearing about pain, and the medical reluctance to address its messy reality, “having social permission to be in pain within that interaction—even if it's not necessarily chronic pain—is really, really freeing. It’s a space to be heard, to be listened to, and to listen to yourself”.

“Having social permission to be in pain within an interaction is really, really freeing. Kink is a space to be heard, to be listened to, and to listen to yourself”

I ask Emma how her research might help improve healthcare for people living with chronic pain. She holds that there is value in simply continuing to rethink disability, especially sociologically, but part of her wonders what else she could do with her findings. One of Emma’s participants joked that spanking should be prescribed on the NHS as a treatment for chronic pain. This isn’t as novel as it sounds: during her research, Emma discovered that one treatment for amputation in the 1940s was ‘limb percussion’: tapping the amputated limb to retrain and distract from residual and lasting pain, “the endorphin rush of the new thing overwhelming the chronic”.

More realistically, Emma suggests her findings could be used to educate providers on the importance of properly recognising and comprehensively communicating pain. Communicating pain fully involves “acknowledging that words are not always the most useful thing. I’d like there to be more space to think about pain as more complicated than: there either is or there isn’t. It’s more messy”.

Ultimately, though, Emma’s research sits within and contributes significantly to critical disability studies, and does not aim to improve the medical system: “there doesn’t always need to be an answer; sometimes the conversation is the most useful thing”. This stance mirrors the plight of many in the chronic pain community, who argue the collective desperation to rid us of chronic pain is a dismissive and often harmful approach: chronic pain, by nature, “is just going to keep going”. So instead of trying to cure it, “let’s see what we can do with it when we stop putting energy into trying to make ourselves better”. “BDSM is a space to not be better, to not be cured . . . it gives you a sense that you can deal with it, even if you go back to feeling like you can’t afterwards.”