Artist spotlight: Becki

Content warning: This article contains discussions of self-harm.

Becki is a multimedia artist and writer from Cardiff, Wales. Her work is influenced by her interests in philosophy, psychology, and esoterica. We connected to talk about art as a coping mechanism, transformative materials, and the power of colour.

Po: Where are you from and where did you grow up?

Becki: I’m from Cardiff, and I’ve lived in South Wales my whole life. My Welsh identity is really important to me. Although none of the adults who raised me speak any Welsh, I’m raising my own son to be bilingual. Culturally, a lot of my family comes from an Irish Catholic background, so I feel deeply Celtic and not at all British.

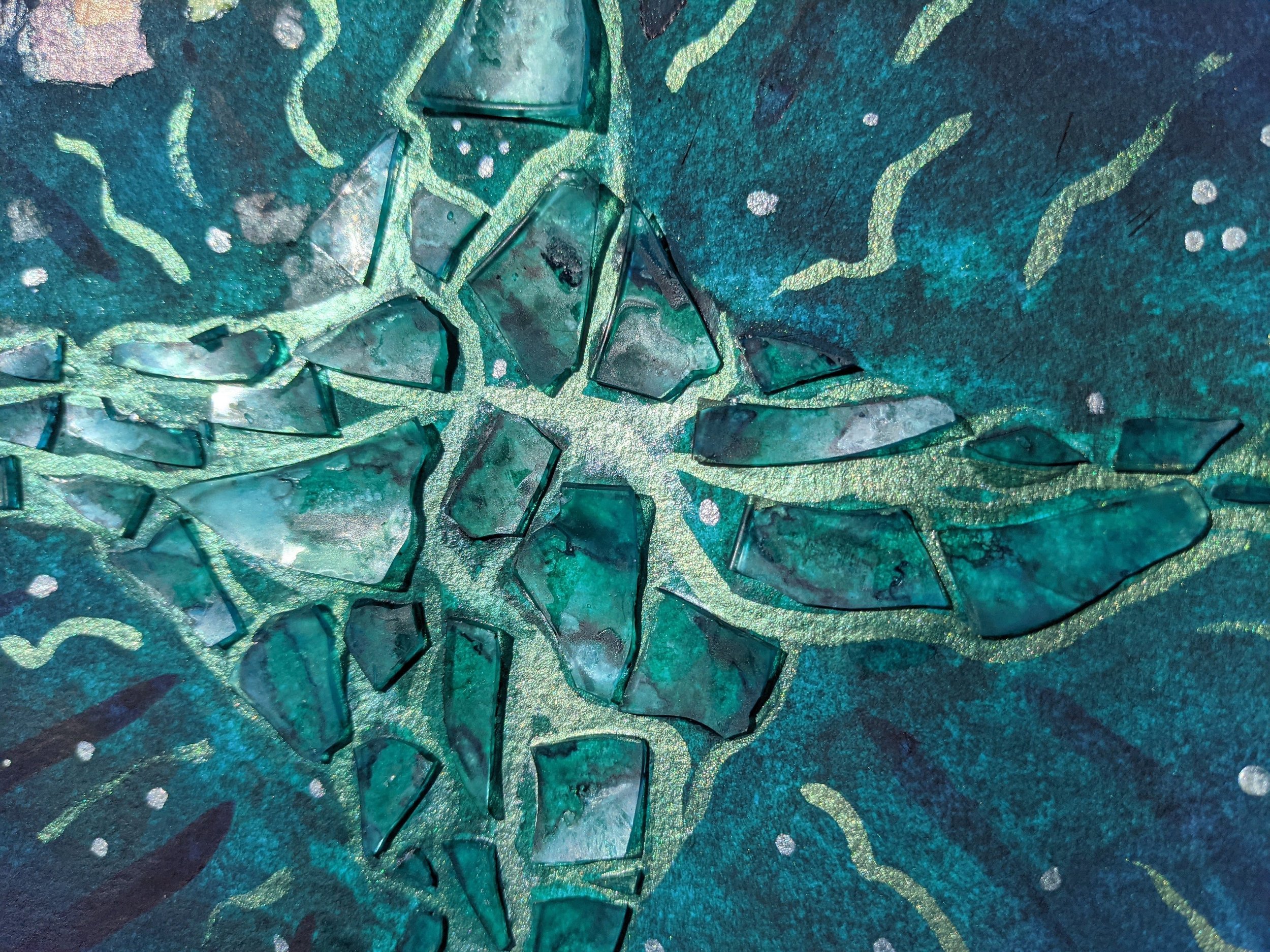

Everything is going to be alright

Image credit: Becki

What place did creativity have in your life when you were growing up?

Creativity was always an escape for me. From a very young age I was a voracious reader, and I used my vivid imagination to create fantasy worlds to play in. But coming from a low-income working-class home, most of the life advice I was given was to study something academic that would lead to a well-paid career and financial security. So, I pursued academic subjects that allowed me to at least think creatively, and gained my degree in Politics and Philosophy from Cardiff University.

When did you start making art on a more regular basis, and what spurred you to do so?

During my degree, art came crashing back into my life after a series of realisations about my health and the support I received as a result. Living independently for the first time was a real struggle for me—I had trouble managing my time, juggling work, studying, and keeping track of all the things I was supposed to do. Eventually I missed an exam because I genuinely just got the time wrong, and I was diagnosed with dyspraxia through the student support service.

I was also very depressed and anxious at university. I self-harmed regularly from the age of 14, but during my first year at university it became a nearly daily habit, and I was drinking huge amounts of alcohol and smoking cigarettes to self-medicate. People who knew me at that time have since told me, “I honestly thought you were going to end up dead.”

Stay here

Image credit: Becki

It was during this destructive cycle that I met Hannah Morgan, and it was literally life changing. Hannah was the first person I’d ever met who had been in a similar position to myself and had come out the other side. She was in the process of setting up Heads Above The Waves, a non-profit supporting young people with mental health problems. Along with her co-founder, Si, Hannah helped me to realise that I had the power to stop hurting myself and to channel that emotional energy in other ways.

As a result of her advice and support, I returned to creativity. At first my creations were very dark—literally and emotionally—as I processed difficult experiences. I didn’t have much money, so I worked a lot with found and recycled materials: collaging with cut up cereal boxes, sweet wrappers, and junk mail. These creations shifted my perspective, and I began to see art as a tool that I could turn to when I needed a distraction or catharsis. I haven’t stopped creating since then.

You are who you have always been

Image credit: Becki

“I began to see art as a tool that I could turn to when I needed a distraction or catharsis.”

You experiment with mixed mediums in your artwork. What do these materials mean to you?

Broken glass, in particular, holds a lot of emotional significance for me. I frequently have accidents and break things, which I now know is due to dyspraxia. But before I was diagnosed, I got into trouble a lot for being “careless”, “thoughtless”, and “ungrateful”. I internalised these criticisms and saw every broken cup as evidence of how deeply terrible I was. It was because of these feelings that I first picked up a shard of a glass I’d just dropped and used it to cut myself.

Glass was my tool of choice for self-harm, and I was never short of it, so using it in my artwork feels transformational, alchemical; I’m taking something with intense negative associations and making it neutral. In my latest collection, I feel like the watercolours represent the soul, or personality, and the glass is trauma. Trauma happens to all of us: it’s undeniable and it shapes the way we develop. But our soul and personality hold the potential of absorbing and growing around these painful experiences to become a more complex and beautiful version of who we already were. I don’t like the idea that “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”; I don’t think survivors should have to feel grateful for the awful things that have happened to them. But I do think it’s valuable and an important part of the healing process to look directly at the trauma and acknowledge the tangible ways it has affected you.

“I don’t like the idea that “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”; I don’t think survivors should have to feel grateful for the awful things that have happened to them.”

The cracks are how the light gets in

Image credit: Becki

Can you tell me a bit about your artistic process: is creativity spontaneous for you, or do you choose a time and place to work on an art piece?

Both! I’ve worked hard to learn to use art as a replacement for self-destructive behaviours or as a reaction to overwhelming experiences. I have stashed notebooks and scrapbooks in every room of the house, and whenever I feel the need, I grab one and doodle or write whatever it is that I need to get out of my head. Sometimes I just grab a stack of magazines and start flicking through and ripping things out with no plan in mind, just to occupy my hands while my mind-body relaxes.

I also plan pieces that I want to make, sketch them in a scrapbook, and then create them carefully over the course of several days. I find that having regular practice gives me the space to keep my mind calm day-to-day. Painting, collaging, building glass mosaics with tweezers: these are my versions of meditation. I can’t sit still and think of nothing, that’s impossibly uncomfortable for me, but I can be present with myself on the page.

Do you create art primarily for yourself?

At first it was mostly for myself, but since I started working with Heads Above The Waves, I began to focus more on the positive side. I didn’t want my art to be a rumination on all the depths of my lowest moments; I want it to be a little beacon of hope and for people to see it and feel that they’re not alone.

On your Instagram page your bio reads “turning wounds into wisdom”. What does this mean with regard to your art?

Still expanding

Image credit: Becki

I actually have a tattoo that reads “turn your wounds into wisdom”. I’ve held onto this idea for a long time: I’m not broken, or damaged—I’m learning. This is the value I can bring to my community: my experience, my healing, the lessons I’ve learned. I want to help people find the path out of their pain.

Unlike a lot of art that centres around themes of pain, madness, and politics, your work is comparatively very pretty and colourful. Is this a conscious choice?

Absolutely. I feel like colour has so much power, and I think there’s already more than enough art that dwells on the darker side of things. For me, I find comfort in numinous colour, and in remembering the scope and depth of beauty that exists. In an ideal world, looking at my art would remind others of this scope and beauty, too.

You identify yourself as Welsh, neurodivergent, chronically ill, and queer. How do these identities overlap and impact your creative process?

These labels are important to me because they are the communities that have welcomed me, held me, and allowed me to discover myself. Along with my diagnosis of dyspraxia, I have Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), and developed fibromyalgia following a pulmonary embolism in 2016. I think there’s a common feeling of relief among many neurodivergent and chronically ill people in finding online communities and suddenly connecting with other people living a similar experience as you. Finding these communities has made my life bearable in ways that I can’t completely articulate, but my creativity is often a reflection of these identities and processes.

You deserve good love

Image credit: Becki

We spoke about the potential of you doing an exhibition with Heads Above the Waves in the future. What draws you to this possibility?

Without Heads Above The Waves, I don’t think I would be an artist today. I might not even be alive. Putting work out into the world where it can reach people could make a tangible change for somebody who needs one. It feels valuable to be both carving this path for myself, and sharing as I go for the benefit of others coming after. I want to prove (to myself as much as anyone else) that it’s possible to live a balanced, fulfilling life as a disabled, chronically ill person.

Heads Above The Waves is a non-for-profit organisation that raises awareness of depression and self-harm in young people. They promote positive and creative ways of dealing with bad days. Advice, positive coping techniques, and other people’s experiences can be found on their website.

For urgent support in the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or you can email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org